Matthew Gamber (b. 1977) lives and works in Boston, Massachusetts. He is the recipient of a Blanche E. Colman Award, a Traveling Fellowship from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the New Photography Grant from Humble Arts Foundation.

Gamber is an Assistant Professor in the Visual Arts Department at the College of the Holy Cross, having previously taught at Lesley University College of Art and Design, Boston College, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Savannah College of Art and Design, Massachusetts College of Art and Design. He has also previously worked on archive and digitization projects with Harvard University and the Boston Public Library for Digital Commonwealth. He is a founding editor of Big Red & Shiny, and a member of Piece of Cake.

It has become something of a cliché to begin articles about contemporary practice in photography by reiterating the ways in which digital technology has transformed our understanding of the medium, pushing photography to places it had never been before. But while this might be true in many respects, it also imposes something of a false continuity on the pre-digital history of photography, one that was by no means apparent then and even now appears more rhetorical than factual. However, these questions about the uses of photography and the sort of roles that it can occupy are also central to the work of Matthew Gamber, questions about the medium and what is does to our understanding of the world around us that do undeniably appear more pressing in light of the changes that have been wrought by this supposed revolution in technology. These challenging questions – and their equally challenging answers, asking the viewer to engage with photography in often unfamiliar ways – might appear somewhat academic; certainly the genre of ‘photography about photography’ has been especially prominent in recent years, but in Gamber’s case this questioning goes to the heart of the perceptual and sociological underpinnings of our encounter with reality, which is in part legitimised through the ‘reading’ of photographs.

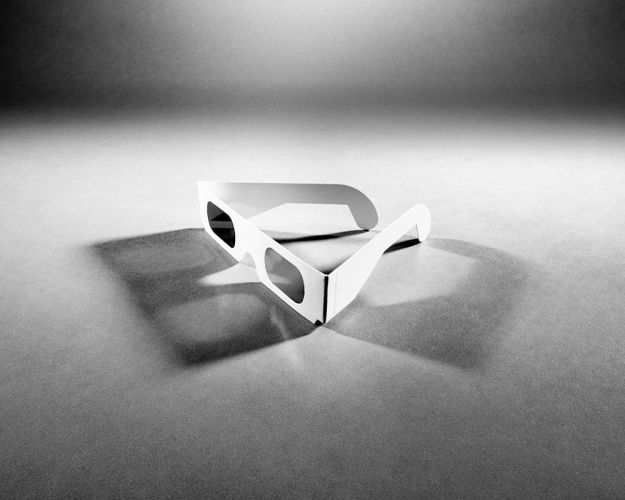

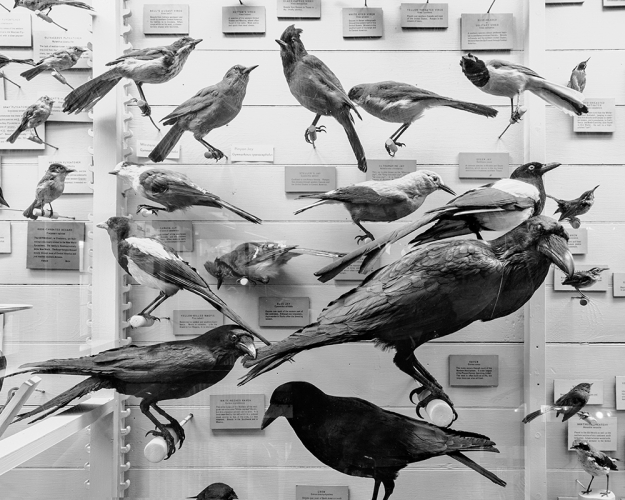

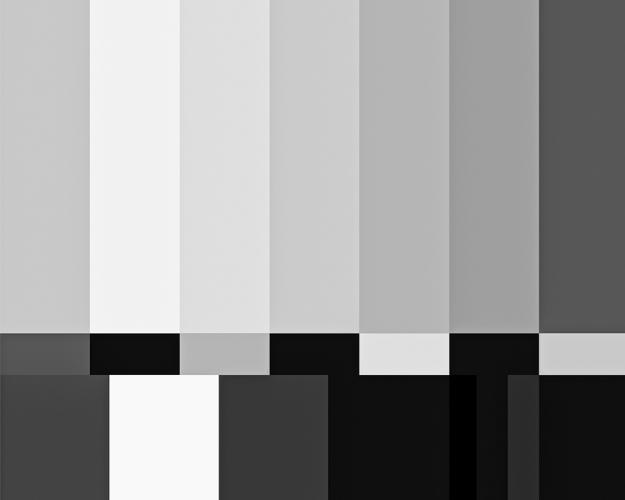

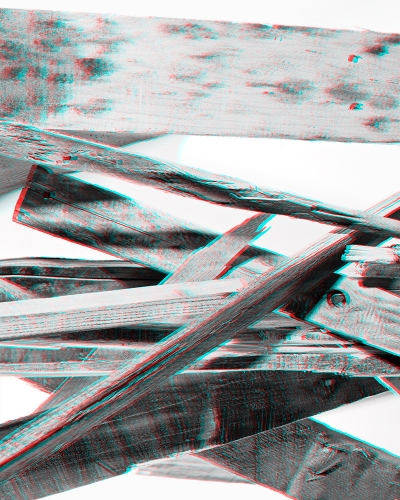

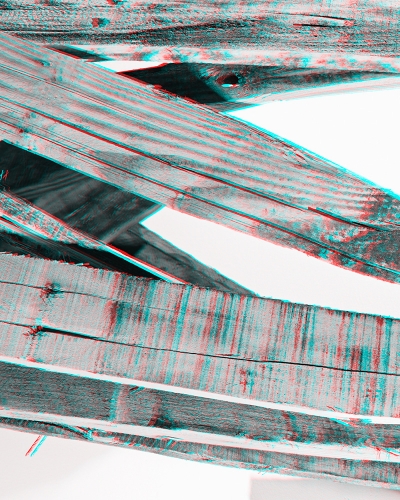

It is also true that in spite of considerable change, the photographic image has retained a uniquely privileged connection to its subject. What our faith in the primacy of that connection obscures, however, is the conditional nature of the relationship between photograph and subject (the pre-existing reality that it depicts). These conditions are both material and historical, transforming what we see in and through the photograph in profound ways. One fundamental aspect of this transformation is key to Gamber’s series Any Color You Like, namely how the shift to monochrome exposes the conditional nature of photographic representation – and even of visual perception itself. By emphasizing the ambiguities that this transition brings up and the extent to which our understanding of each picture is actually predicated on an absence of information, Gamber is articulating some of the most paradoxical aspects of the medium, where the monochrome tonality functions as a kind of stand-in for its essential conditionality, which is, after all, not just a simple matter of colour, but also of how we are being shown a particular reality. At the same time, a photograph definitely has a sort of informational role – it can describe what something (an event, an object) looks like, but the caveat that Gamber astutely adds is that a photograph will only tell us what something looks like when photographed and that distinction is a considerable one.

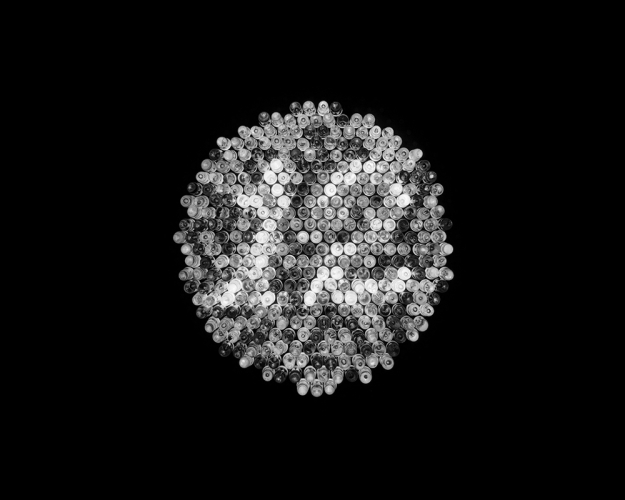

His interest in a pseudo-scientific vocabulary continues with a more recent work, Basic Ingredients of a Complex World. Here the pictures are far more diverse stylistically, but undoubtedly draw upon the same impression of rigour that has marked Gamber’s work so far and that attests to his understanding of the medium as a set of choices about the manner in which something is shown. The fact that these choices are not always made consciously does not make them any less significant; it is precisely because the photograph appears to function transparently in most cases that Gamber’s pointed use of this informational vocabulary is so effective. By foregrounding the conditions that make the pictures ‘work’ as information he is allowing us to see those conditions for what they are – and indeed, making us aware of the fact that they exist at all. But in this case they have been unmoored from the structures that would otherwise have rendered them legible, so what we are left with is the ambiguity of a seemingly exact description without any corresponding function. As photography is a kind of knowledge, its ambiguities are shared not only by those areas where the medium is used factually, but also every way in which knowledge is possible. Gamber’s interest in the discourse of photography seems to be aimed squarely at understanding what that means.