published by Kehrer, 2015

essay by Natasha Christia

Designed by Henning Rogge, Regine Petersen

3 hardcover books in slipcase / 20 x 25 cm

19,2 x 24 cm

144 pages

78 b/w and color ills.

ISBN 978-3-86828-597-0

Euro 49,90

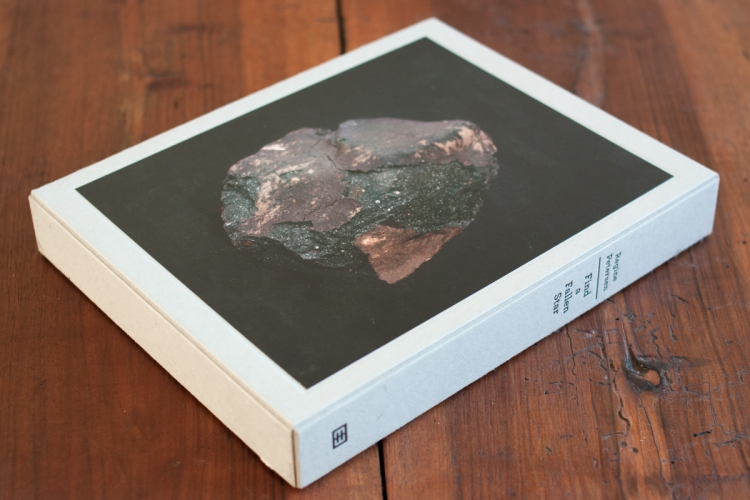

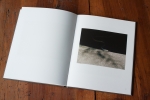

Although the urge to tell stories with photography is a persistent one, the medium itself seems oddly resistant to narrative, at least in the familiar sense. Photographers are obliged to find ways of arranging individual images into sequences that are more than telling than their individual components, largely in recognition of the fact that single images consistently fail to encapsulate complex situations; we need more than one view. Regine Petersen’s Find a Fallen Star is significant in this respect, as it is, essentially, an attempt to tell the same story in three different versions at it occurred in different places to different people and at different times. The stories themselves then become a way to reflect on those places and times, using a blend of archive material and her own quiet photography. From the outside at least the books are formatted identically and all three are housed in a cardboard slipcase with a tipped-in cover image. The mix of found material and original photography that makes up the work has been an especially prevalent strategy in recent years and is intended to tackle the narrative short-comings of photography. It is a means of addressing historical situations where the sort of description that photography normally excels at simply isn’t useful, although its popularity has also tended to obscure those cases where an equally inventive solution might have been found.

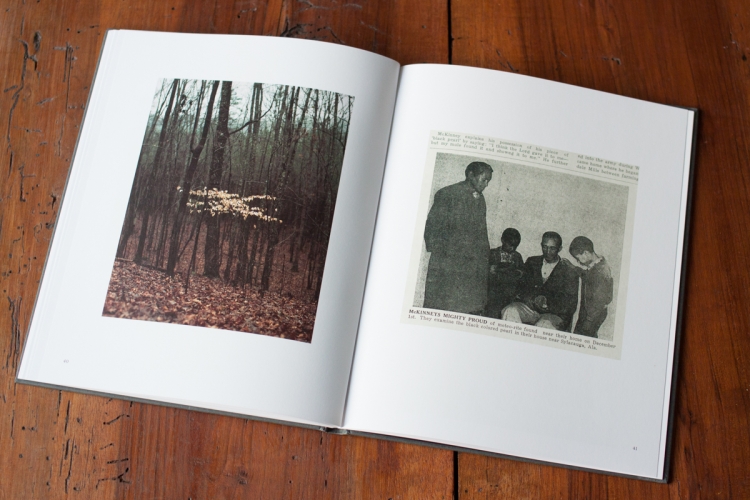

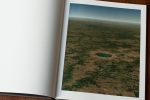

Petersen’s approach is to use this method for three different stories, in the first place because the events depicted are not recent and she wishes, indirectly, to comment on the times in which they occurred, but also to test the limits of her chosen strategy, to see how many variations can there be of this basic ‘archival’ format. The differences between the individual books that make up the project are not necessarily large, but they are telling in their own way. As the title implies, the central event of each book is a meteorite falling to earth, not something that is readily photographed, except perhaps by specialists, but of course Petersen isn’t really concerned with showing the fall itself so much as the circumstances of its aftermath and the resonance it produced at different historical moments. In fact, these chance events become a way for her to examine the wider social contexts in which they occurred. She does this by tracing a web of incidental connections between the original meteorite strike and what effect it had on those involved. Her main point is that these singular events can be shown to have revealed tensions implicit in lives and communities, whether these be social, economic or even psychological, that otherwise would have went unnoticed.

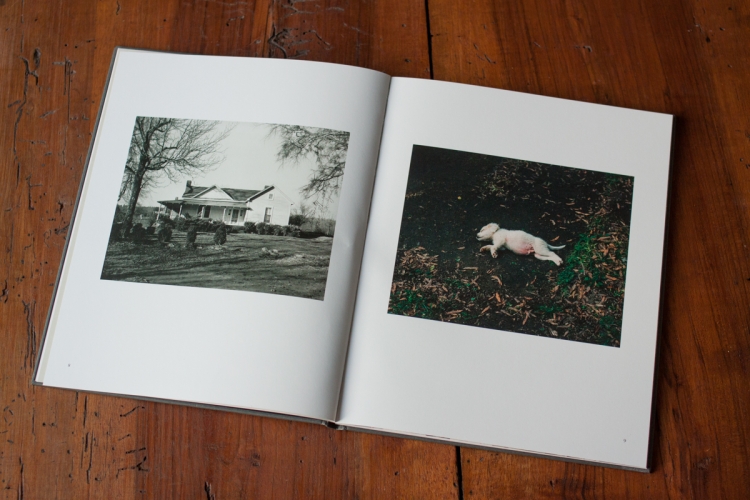

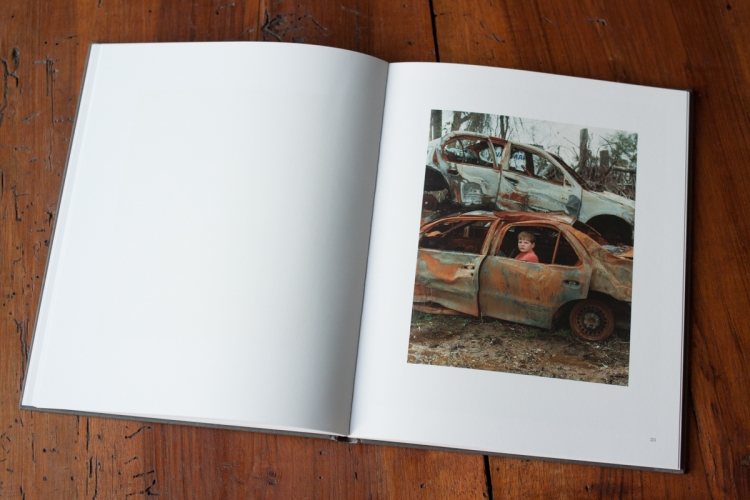

In Stars Fell on Alabama, which might be considered the opening volume of the three given that it is the earliest strike chronologically, concerns the effect of that fall on small town Alabama in 1954. One fragment entered the roof of a house and struck its occupant, Ann Hodges, while another was found by a black farmer named Julius McKinney about five miles from where the first fell. What Petersen is looking at here is the ways in which these people responded to their extraordinary encounters and what the reaction of those around them was; she uses these reactions, summarized largely from archival materials to infer something about the social situation of 1950s America. By its nature the narrative being presented here is bound to be somewhat ambiguous. For the most part we are left to construct our impression of these events around the gaps in Petersen’s account, a consequence of her archival strategy – even official memory is shown to be partial, while personal recollection is often distorted. But this tracing of events does still give us some sense, not just of what the meteor set in motion, but how it can be understood as a sort of catalyst that released tensions in the people and communities that were touched by it. The suggestion is that Mrs. Hodges was adversely affected by the notoriety brought by her being the first recorded instance of someone hit by a celestial object, while McKinley sold his fragment for an “undisclosed†sum that we can probably assume wasn’t all that much. But for the purposes of the book it is the difference in how their respective experiences are reported that is the most striking.

The role played by Petersen’s own photography in the narrative is sometimes harder to discern; after all these books could conceivably have been made with just the text and archival material. This is especially true of her portraits, which, though generally well done, are not really anchored in the narrative, except by their captions asserting some loose relation to the events being recounted (usually that the person is a descendent of those involved) but this is not something we can be expected to understand from the pictures themselves. By contrast, her environmental studies have far more resonance in setting a tone for the narrative, quietly suggesting a cumulative kind of unease that shadows our reading of the archival material. So in that sense the relation between the two elements of the narrative is crucial, though their integration is not always as smooth as it could be. In all of the books, Petersen is clearly working through the possibilities of this archival form, which is needed to talk about something that can’t, in most ways, be directly seen and varies according to the demands of the story. Her own pictures have been calibrated not to overwhelm the archival material and to play, essentially, a supporting, if hardly minor part. In that, they are largely successful and the same basic pattern repeats with the other two volumes of the set, though it is perhaps most resolved in the second book, entitled Fragments.

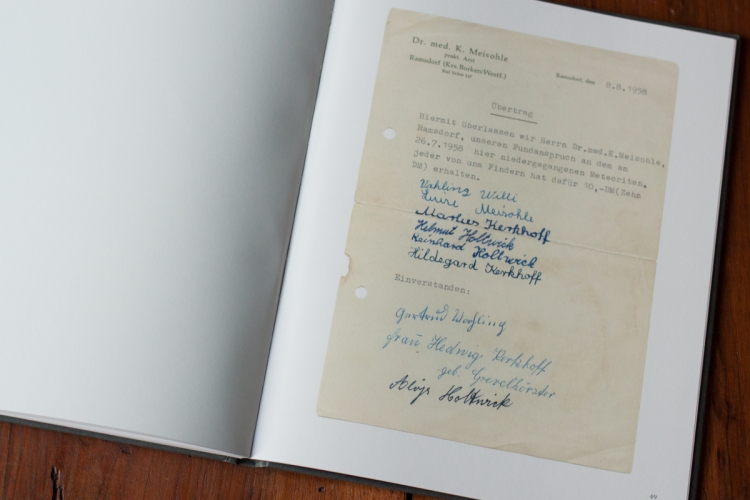

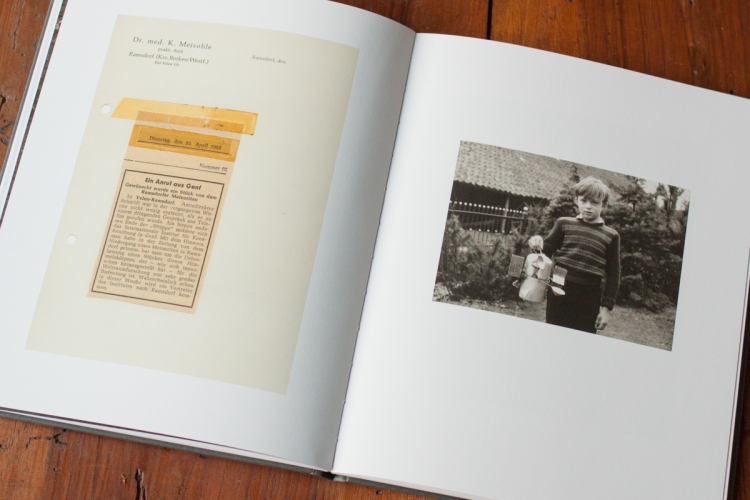

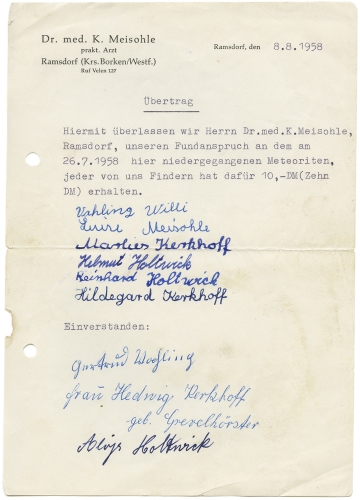

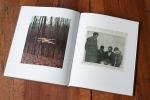

Here the setting moves to Germany, just a few years after the events of the first book. A number of children seemingly hear rather than actually observe the fall of a meteorite. When setting out to investigate they find a crater and the next day they dig an object up. In the course of this amateur excavation the meteorite is broken into several pieces and is divided between the children. The story is recounted by those witnesses, now of course much older and some of whom Petersen has photographed in her restrained style. Compared to Stars fell on Alabama, their account lacks much obvious drama and the strike itself seems to have been a minor, though exciting event for them. Their recollections are perhaps influenced by a retrospective, adult practicality and there is also a notable variation between their accounts, as the passage of time has coloured the memory of these events. Petersen allows this variation in their accounts to remain visible in order to fore-ground the extent to which narratives are necessarily positioned by how they are told. The subtext here is of a divided country on the fault line of antagonism between two global superpowers and it’s safe to say that the imaginations of this post-war generation couldn’t help but be shaped, at least implicitly, by that charged context. In fact, Russian space exploration is clearly alluded to by one of the witnesses, so Petersen is again telling us something about the historical situation; this is not just a description of events, but accounting for a mood submerged within the archival records and for which the meteor serves as a narrative focal point.

The most pointed of her archival inclusions here is a snap-shot of a boy with a homemade contraption identified as a model (or maybe a pastiche?) of the Sputnik satellite. It’s also hard not to see the division of the meteorite between the children as suggesting the post-war division of Germany into different zones of influence. Among the constraints of the archival strategy, however, is that it doesn’t allow for any real commentary on the events that it brings to light; that role falls to Petersen’s own photography, which, as we have seen, is deliberately restrained in order to set the tone for these archival excavations. So, although this volume is perhaps the most resolved of the three in terms of the integration of the found material with the original photographs it also inevitably comes up against the limitations of the form, in so far as Petersen has little scope to take an explicit position on the issues under discussion. This is evident in the last volume as well, which is maybe also the slightest in terms of its construction, concerning a fall in India in 2006. The subtext for this work is, of course, the widening gulf between what is known as the ‘developing’ world and our own, supposedly ‘developed’ one. Even here the men who witness the fall think it’s a rocket directed at the near-by nuclear installation. This plant also features in a snippet of a remarkably snide email chain concerning the object (they opt for it being nuclear slag rather than of a celestial origin).

On the whole, Petersen has fashioned a solid and yet evocative work from the materials at her disposal, forging unlikely connections between a series of chance, highly portentous events and the historical circumstances in which they occurred. These connections reveal the tensions implicit in the places, times and lives surrounding each event. This is perhaps the ideal use for Petersen’s archival strategy, whatever its limitations, in that it can make visible what has gone unseen and is long past, while her own pictures set a tone for this recovery in an often very telling way. The sophisticated relation of the archival material to her own photography is a testament to the potential of this approach in the right hands. It’s also true, however, that the jump from the 1950s in the first two volumes to the (near) present leads to a feeling of asymmetry that is not satisfactorily resolved, even if the books are still unified by the use of repeated visual motifs, such as the pictures of isolated animals, itself a suggestive metaphor for our own diminutive role. Accordingly, the reconsideration of the past that is at stake here relates to the desire and the incapacity to make sense of our lives; we have long turned to heavens for a clue to earthly events and Petersen has deftly connected those two realms.

www.reginepetersen.com

Buy the book here